RL Stine doesn't believe in ghosts. Or a vampire, a Sasquatch, a wisecracking demonic ventriloquist dummy, or any of the other supernatural creatures that appear in his best-selling children's horror series Goosebumps . He was shocked that other people did this. Stine told Booster that during readings, he likes to tell a ghost story and then ask the audience if anyone has ever had a run-in with the undead. “You couldn’t believe how many people raised their hands,” he marveled. "I said, 'No, not on TV'... Their hands [went up] and all these kids thought they were seeing a ghost. It was really amazing."

But that doesn't mean Steyn hasn't encountered the unexplainable. One day nearly 40 years ago, when the master of tween horror was working as a humorist, writing children's joke books and editing a teen comedy magazine called Bananas , a colleague walked into Stine's office at work. Ask him how old he is. he is. "I said I was 38 years old... when I said that, I floated up and I could see myself saying this from the ceiling... I looked down at myself and said I am 38 years old... and then I It came back and I was like, 'What just happened? ' I was a little shocked, to be honest."

Since then, Sting has had no more out-of-body experiences. But decades later, his assessment of the experience would not seem out of place in one of his books, in which horror and comedy often mix in equal measure: He left his body because, he said , “It’s such a scary number and to me, 38 is just so scary.”

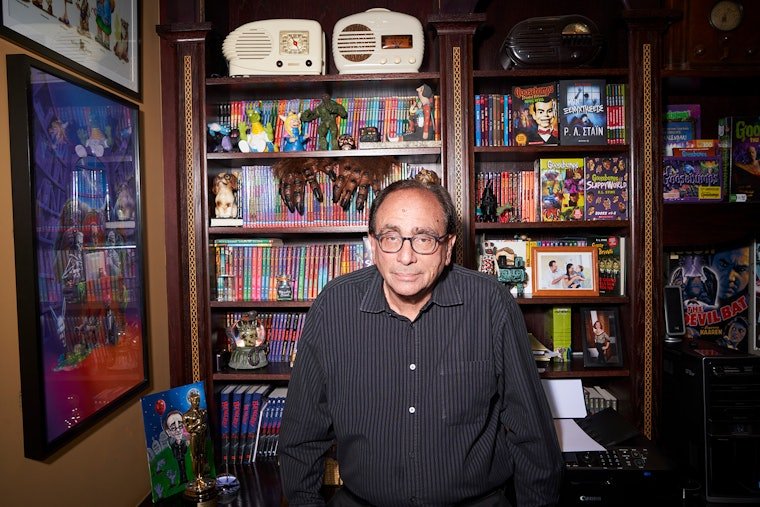

Stein is now 75 years old, not far from turning 38. He hasn't been a comedy writer for long, either - ever since his 1986 teen horror debut "Blind Date" became a bestseller and changed the course of his life. But for him, comedy and horror are more closely related than you might think. "I'm never afraid. Terror doesn't scare me," Stine said. “I’ve never been afraid of movies or Stephen King books. I love them, but I don’t feel that way,” he notes as we sit in a bland library in his Manhattan apartment at this point. All things macabre are sequestered in the halls of Stine's study, which may be the only room in all of New York City that simultaneously houses a giant papier-mâché cockroach, a jar labeled "Monster Blood," and a crafted into a dummy that looks like. Like Stine, she has also won multiple Nickelodeon Kids' Choice Awards. But in the library, the shelves are filled with gorgeous books and a built-in rolling ladder, giving the place a more Beauty and the Beast vibe than Far From the Basement !

"With Goosebumps , I really didn't want to scare anyone. So if a scene starts to get really intense, I always add something fun to it," he said. Stine's drive to make readers laugh even appears in the series' infamous cliffhanger chapter endings: "Chapter endings in my books are all punchlines."

That's not to say the comedy always appeals to the series' loyal young readers, who may not be old enough to see the comedy inherent in haunted masks or the caves inhabited by evil ghost children. "People say to me, 'Oh, after I read your book, I had to turn all the lights on, I had to lock the doors.' To me... horror always makes me laugh," he explain.

Perhaps this perspective is the secret to Steyn's astonishing success. Growing up in Ohio, Stine was a regular at Saturday afternoon horror movie matinees, but he never thought about making his own horror films. Instead, he became single-mindedly interested in humor writing, first publishing a comedy magazine for friends while in school, and later spending ten years editing Banana . “That’s been a lifelong dream of mine,” Stine said. "When I finished 'Banana ,' I just thought the rest of my life was going to be easy. I didn't know it."

Everything changed in 1985, when he had what was supposed to be an ordinary lunch with an editor he knew. The editor looked shocked. She got into a heated argument with a teen horror writer she'd been working with. She told Stine she would never work with that particular writer again—and that he would do just as well writing a teen horror movie. In short, "She gave me the title because she was angry with him."

She asked him to go home and write a book called "Blind Date." "At that point in my career, you said 'yes' to everything. You were afraid to say 'no,'" Stine said. "So I said, 'Sure, no problem.'"

After running into a bookstore to research the teen thriller scene, Stine decided he wanted his book to be different—"younger, cleaner, and less vicious." Stine then spent three months making it Blind Date - "That's a long time before I spend money on a book" - became an instant bestseller when it was published. "I'm like, 'Wait a minute. What's going on?' I've never put all my joke books on this list."

When his novel "Twisted," about a group of evil sorority sisters, topped the charts again the next year, he had a revelation: "I said, 'Wait a minute. Forget about the funny stuff.'" I've been scared ever since. "

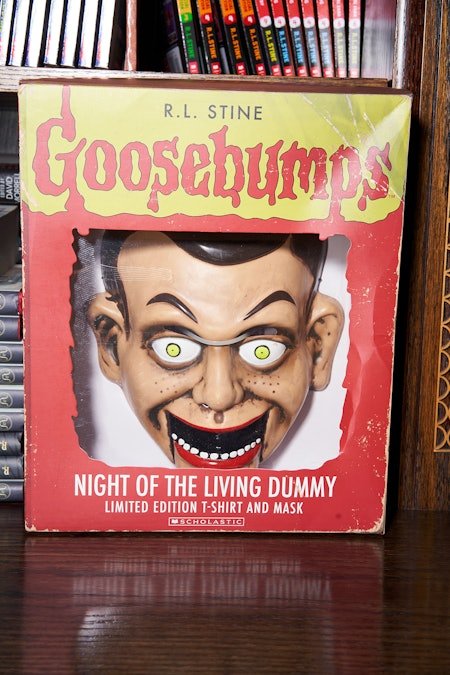

But nonetheless, as Stine tells it, he almost didn't write Goosebumps , the 26-year-old series that made him a household name, sold more than 400 million copies, and spawned a TV show, Disney World attraction and two movies - the second of which , Goosebumps 2: Haunted Halloween , opens in theaters on October 12. By the early 1990s, Stine was successfully writing standalone horror novels and the YA series Fear Street, writing a book a month. But when his editors approached him with the idea that would become Goosebumps , his first instinct was to give up. “My editors said, ‘No one has ever tried a horror series for 7- to 12-year-olds. We should try that.’ I said, ‘No, I don’t want to. "That's the kind of businessman I am, right?" he worried. "It's going to screw up Fear Street. I have this teenage audience, and I don't want them to start thinking I'm childish."

But constant prodding from editors convinced Steyn to agree that if he could come up with a good title, he would try it. He wrote the first four Goosebumps books after seeing the words "Goosebumps Week" in a TV commercial, which were sold to bookstores "and just sat there. Nothing. I thought, if we use computers today And other things that do that, they'll pull them off the shelves because they don't sell."

Stine's audience at the time was mostly teenagers and didn't want to read a fairly innocent story about evil toys and haunted cameras, and young readers had no idea who he was. But by the time the fourth book was released, word of mouth from kids led to a rebound in sales. "Somehow the kids discovered it," Stine said. "I don't know how - some secret children's network. Kids would buy it and love it and then go to school and tell other kids. There were no ads." They just took off.

It's no surprise that the entire fate of Goosebumps hinges on the title, as Stine's creative process hinges on the title. He would often get the title of a book and work backwards from there. "I was walking another dog in the park and this phrase popped into my head: 'Say cheese and die.'" I was like, "Wow, what could this be?" If there was an evil machine What to do with the camera? What if some kids discovered the camera and it captured something bad happening in the future? That's how I develop the story. "

But these books are not guided solely by creative instinct and fantasies of evil cameras. Stine also developed detailed outlines for each book, including dialogue and plot-twisting chapter endings. These outlines are typically 20 pages long and take a week to complete—a serious time commitment for a writer who writes 2,000 words a day. “I hate outlines,” Stine said. “But now I can’t function without it.”

These outlines are also where Stine's collaborators come into play, including his wife Jane, who was also his longtime editor. "I had a lot of editors, a lot , which was lucky in a way," Steyn revealed. "But my outlines were often rejected. Sometimes I would spend almost as much time on the outline as on the book because I had to do two or three versions." If the outline was approved, "I would almost know the book The book will be fine." What if his editor didn't think the outline would make a good novel? "The sad thing is, they're always right. They're always right."

After Goosebumps was first published in 1992, Stine worked on that series and Fear Street simultaneously, writing a novel in one series or the other every two weeks. "Now I'm like, 'How did I do that?'" But Goosebumps' success didn't shock him until he got stuck in traffic on his way to a book signing in Columbus, Ohio. "I was really nervous that I wouldn't make it to the store in time, and I looked around and there were all these cars... filled with kids. I was causing a traffic jam. This was my traffic jam. That's when I knew."

As the '90s dawned, the Goosebumps craze was in full swing. In 1995, the Goosebumps television show debuted as part of Fox's after-school programming. Stein was too busy writing and doing journalism to work on the show; Jane reviewed the scripts, a role she later expanded into by becoming an executive producer on Sting-related shows The Nightmare Room and The Ghost Hour . However, he still found time to visit Disney World's Goosebumps Horror Park Show, which opened in 1997. The attraction includes live stage shows and a mirror maze, which excited Stine, a Disney fanatic who said he would "want to live in the park."

As the decade came to a close, the series slowed down. The final entry in the original series , Monster Blood IV , was released in late 1997; spin-off series, including Goosebumps and Choose Your Own Adventure , ran between 1997 and 2000 out. The Disney attraction closed in 1998, the same year the Goosebumps TV show stopped producing new episodes (although reruns would remain a staple of children's television for years to come). He decided to take a break from the goosebumps.

He began publishing the similarly themed Nightmare House series in 2000, "which was an unbelievable bomb. We didn't sell 10 books. They were good, too. They were Goosebumps books, they were just called Nightmare House . I always wondered why, kids, they didn't want to make it a good TV show, but it only ran for one season."

Stine found the answer while holding a book signing in Boston: A passing child rejected a book, declaring, "I don't want nightmares." Then, Sting said, "I realized that might not be the best name."

Over the next few years, Stine created a number of other series, including Mostly Ghostly, a comedy ghost story, and Rotten School , an all-out comedy about some very annoying kids. But he never quite ditched Goosebumps . When he got a call from Scholastic asking if he would be interested in starting the series again, he decided to give it a try, and in 2008 he launched the first ongoing Goosebumps story: Goosebumps Horrorland . Write, I thought, but that's fine... And then we got popular again, this old series. "

The 2015 Goosebumps movie brought about a comeback for the series, with Sting reporting that sales tripled upon its release. “The power of film is amazing,” Stine said. "I give talks all the time. I have a lot of audiences now just because they think they're going to see Jack Black." Black flew out during a snowstorm to meet Sting and study his mannerisms, playing a "sinister version" of Sting. "Then, while filming, he played me like he was Orson Welles. I said, 'Jack, I don't talk like that. I'm from Ohio.'"

Sting attributed Goosebumps' initial success to the fact that people enjoyed being frightened when they knew they weren't actually in danger, as well as "a surprising amount of luck." It's these two factors that have brought him back into the public eye 26 years later, where former Goosebumps readers took their children to read the books with them, and now children are reading the books themselves. “It’s actually great,” Stine said. "I always say, I scared many generations of people. How lucky is that?"